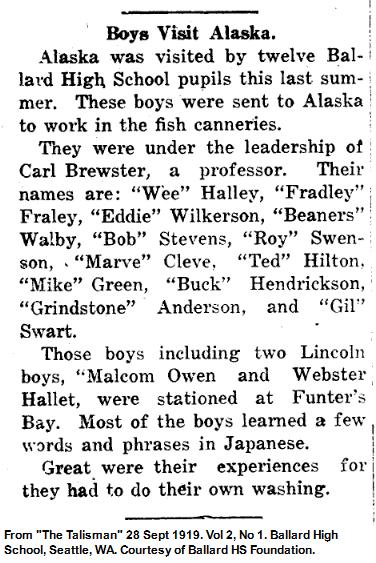

The Funter post office opened in July of 1902. Located at the Thlinket Packing Co cannery, It served local residents, cannery and mine workers, and outlying homesteads and fox farms. I’ve previously mentioned the post office in discussions of communication and mail boats.

Photo by Harold Hargrave. Undated (post-1941). Courtesy of Alaska State Library, Place File. ASL-P01-3753.

Even before a formal post office was founded, a number of mail boats would stop at Funter on a regular basis to serve the mines there, relying on passenger and freight traffic to cover their costs.

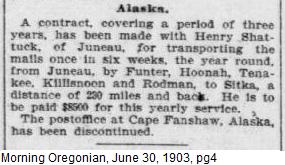

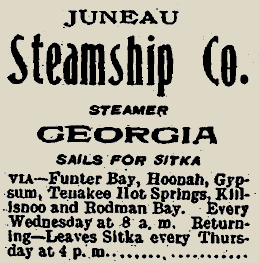

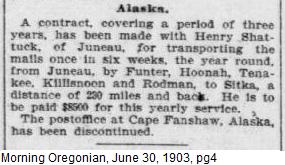

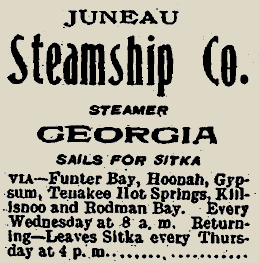

An article in the January 1903 Daily Alaska Dispatch noted that Funter Bay had a post office, but did not yet have a contract for mail delivery. In March of 1903 the assistant postmaster general for Alaska reportedly was considering “the establishment of better mail facilities for Funter post-office” (Daily Record-Miner). By June there was an initial contract with Henry Shattuck to deliver mail every 6 weeks. Shattuck reportedly arranged to buy the steamer Prosper from the Alaska Steamship Co in July of 1903, then formed the Juneau Steamship Co in August and decided to buy the Georgia instead. He is better known for his real estate and insurance ventures, but maintained ownership in various mail boats for some time as well.

Various boats which carried the mail, either under government contract or on an ad-hoc basis, included the Flosie, Rustler, Georgia, Seolin, St. Nicholas, Ramona, Estebeth, Forester, Margnita, and likely several others.

In 1906 a government report described “A cannery, a store, and a post-office with weekly mail service via Juneau” at Funter Bay.

1906 Mail Steamer ad

A 1912 Dispatch article discussed the mail service to outlying communities, including Funter Bay. Mail from outside was received in Juneau on steamships, then sorted and distributed to mail boats serving the surrounding area. The Juneau postal staff complained of the burden of meeting late or irregular boats.

1915 Advertisement

The Funter post office served an area extending across Lynn Canal to Point Couverden (with several fox farms), and down Mansfield Peninsula to Hawk Inlet. A cannery opened at Hawk Inlet around 1911, and several mines were operating around 1900, but there was no post office there until 1913. Prior to that year, someone had to row 15 miles to Funter or walk over the mountain to pick up the mail. This was not without risks, as mentioned in a previous post, a Mr. J. Caper fell and broke his ankle while crossing the mountain on a 1910 mail run.

Mail at Funter was general delivery, recipients had to visit the post office to pick up their mail. Addresses consisted of the recipient’s name with “Funter, Alaska” or “Funter Bay” underneath, zip codes were not used until the 1960s. Much of rural Alaska shared the 5-digit 99850, Funter Bay’s full zip code was 99850-0140. The USPS serial number for the Funter post office was 05544.

Freight could also be sent this way, although the following letter (found in government archives) notes that the mail boat would not carry certain items like blasting powder.

This history of postmasters at Funter is somewhat patchy, and seems to include several people who resigned or left suddenly, leaving other residents to fill in until being officially recognized by the USPS. A list of Postmasters with their start dates is below, based on various government and journal records as well as Melvin Ricks’ Alaska’s Postmasters and Postoffices; 1867-1963.

Postmasters at Funter Post Office:

-James T. Largan, appointed July 3rd 1902.

-James T. Barron (Cannery owner), appointed June 24 1904. Received $10.00 in compensation for the position. (ref) (As Barron was only on-site in the summers, there may have been a cannery caretaker covering the position unofficially in the winters, handling mail for the mines and other residents).

-William N. Williams, appointed 5-7-1926. Listed as the cannery superintendent in 1929 (per Pacific Fisherman, Vol 27, 1929).

-Raymond A. Perry, appointed 5-13-1930. Resigned in June of 1931, Clarence Withrow or Charles Otteson suggested as replacements.

-Clarence A Withrow (or Winthrow?). Appointed 6-29-1931, status changed / “assumed charge” again on 9/30/1931 (perhaps confirmed as permanent from a temporary status?). Also a cannery employee. Taken ill with appendicitis in November of 1934, requiring an operation (per Pacific Fisherman, Vol 32, 1934).

-Burdine H. Carroll. Appointed (took over after Withrow fell ill?) on 9-12-1934, “Assumed Charge” again 11/17/34 (again, this probably indicates the date he was confirmed as permanent). Resigned without official permission 10-1-1939. Some genealogical information is here. According to the Petersburg Press, Carroll was appointed in October.

-John H. Hibbs, appointed 10-24-1939, also “Assumed Charge” / confirmed 11-19-39. Died in office, no date given, probably 1941.

-Hans Floe, appointed 7-8-1941. As with predecessors, “Assumed Charge” 9-19-41. Removed from office (no date, probably 1944). Employee of the P.E. Harris Packing Co, who owned the cannery at the time. Had previously been the superintendent at the Hawk Inlet cannery (per Pacific Fisherman, Vol 39, 1941). According to Kinky Bayers’ notes, Hans came to the US from Norway in 1905, started with P.E. Harris in 1911, and died in 1947 at age 61. His wife was Marie Hansine Floe and daughters were Marie, Odney, Haldis, and Agnes.

<Post office discontinued in 1944, effective December 31st, but order rescinded on November 27th>

-Harold F. Hargrave, appointed 11-30-1944. (Some sources say he served as Postmaster starting in 1941). AC/confirmed 1-1-1945. May have “officially” been the postmaster until ~1955 with others filling in during the later years. Lived at Funter until the 1980s.

Harold Hargrave at Funter Bay in the 1940s. Photo courtesy of Alaska State Library, Place File, ASL-P01-3842

-Virgil S. Aubert. Unlike predecessors, he is noted as “Assumed Charge” on 11-6-1953, with no formal appointment. He is listed as “Acting” Postmaster on 12-14-1953. May have been filling in for Hargrave. Some genealogical information is here.

-Stanley Warnock. Also “Assumed Charge” on 7-9-1954, without a full appointment, listed as “Acting” 8-6-1954, formally appointed 8-5-1955, and again “Assumed Charge” 9-30-1955. Probably the same person as “Curly” Warnock who lived in Funter Bay with his wife Cora (per Lazette Ohman).

The American Philatelist, Volume 68 of 1954 notes that:

“Funter is a mining-fishing town on Funter Bay, Admiralty Island, at the mouth of Lynn Canal. It was named in 1883 by Dall for Captain Robert Funter, an early explorer-surveyor. Mining, hunting, fishing, and trapping provide work for the employables among the ten white and Indian residents. There are no schools or churches. Office opened July 3, 1902 (James T. Largan). Present Postmaster, Harold T. Hargrave.”

After the cannery stopped regular packing operations in 1931, a year-round watchman remained on site. He operated the company store and the post office. The postal guide for 1931 noted that it was open year round, but did not issue money orders. The company store remained open, and the property was still used for fish trap and vessel maintenance.

In the 1940s the post office was inside the company store at the cannery. It was reportedly a partitioned room in the southeast corner of the building, which also housed the canteen and dining room.

Below is a WWII-era postal cover with Funter postmark. The “Emergency Flight” stamp appears to be a reference to Emergency Air Mail, a federal law allowing air mail at ground postage rates for communities cut off from normal surface mail. This was intended for communities affected by floods or other problems, but became popular in rural Alaska. It seems to have been common to mail these to the nearest major post office (in this case, Juneau), then have a forward or return address for the final intended address.

Air mail began appearing around the 1930s, with the government experimenting with different air carriers and contracts for rural service. A 1947 advertisement for Alaska Coastal Airlines notes that “Air Express” service was available to and from Funter and other small communities by request on a variable schedule.

After WWII, the post office was apparently in a separate small building for some time. This building had been the US Fish & Wildlife Service office during the Aleut internment.

The Funter post office was discontinued for the second and final time on April 19th, 1957. After the post office closed, Funter Bay became a mail stop or drop, the cannery watchman would meet the weekly plane at the dock and residents could pick up their mail at his residence. There was no longer a paid position under the USPS, and mail was postmarked in Juneau.

Sometime after Hargrave’s tenure as postmaster, a cannery watchmen and his wife apparently operated a house of ill repute at the property. By some accounts there was an illegal bar and even occasionally “ladies of negotiable affection” (as Terry Pratchett might say). They also supposedly ran some kind of mail-order scam against Sears and other catalogs. I will try to expand on this in a future post as I find more details!

The watchman in 1972 was Scotty Todd, a retired mine driller. Reportedly when the mail brought his social security check he would drop everything, jump on the plane, and go to Juneau bars until the money was gone. Neighbors would pick up and sort the mail and turn off Scotty’s generator on the occasions when he disappeared.

My Dad provided some information on mail service in the 1970s:

“The Forester was the first mail boat I rode on to Funter in 1972, owner/operator was Dave Rischel (sp?). Then he got the Betty R, had a hell of a time getting it Coast Guard approved. The Forester was approved amazingly enough with 4 automatic bilge pumps and one was always running. Dave did the run to Angoon, Tenakee, Hoonah, Elfin and Pelican and of course all the little places where anyone lived like Funter, Hawk Inlet. So when the Ferry system started up Dave got put out of business….

When I first moved there the mail boat came once a week (weather permitting). You would give Dave your list and he would buy what you wanted and charge a minimal fee. Everything from food to bringing me the plywood for my dory. We had twice a week plane service also, which was pretty handy for getting back and fourth to town. Seat fare was something like $20. Per usual lots of drinking and talking at the cannery when you got the mail from Scotty and then Jim and Blanche.”

Around 1978 the Federal government began “Essential Air Service” aka “Essential Air Transportation” which guaranteed weekly mail delivery to Funter Bay and other rural Alaskan communities. This service continues in many rural communities today.

Jim and Blanche Doyle took over the caretaker job and the mail sorting around 1973 or ’74. After they moved across the bay (around 1983), mail planes generally came to the beach at Crab Cove. The actual spot depended heavily on the tide, weather, and any passengers. Outgoing letters and packages could be left with whoever met the weekly plane. Absent residents could pick up their mail from the big mail box near the usual spot for the plane to come ashore

My Dad’s photo of the post office and “Postmaster” Jim Doyle in the 1970s deserves another use!

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts