As mentioned in my prior post, the Thlinket Packing Co had a cannery tender named the Anna Barron based at Funter Bay, named after James and Elizabeth Barron’s daughter Anna. The cannery also owned a number of other vessels, many named after people in the Barron family, but the Anna is best known (for such an obscure topic as Southeast AK cannery tender vessels), since it appears in numerous publicity photos and postcards of the cannery.

The October 1920 issue of Pacific Motorboat mentions that the Anna Barron had three engines which were overhauled that year. The HW McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest describes her as being 77ft long, built in Astoria in 1902 for the Thlinket Packing Co, fitted with a compound (9 1/2, 20×20) engine developing 130hp. Her merchant vessel registry number was 107759.

Today in Funter Bay, there are two wrecks of midsize boats (or parts of them) visible on the beaches. Both of these are locally referred to as “tugboats”, and I had always heard they were cannery boats. One is located in Scow Bay (AKA Coot Cove), and one is on Highwater Island (also called Crab Island on some state survey maps, although I’ve never heard it called that).

The three photos above show the Coot Cove wreck. There’s not much left aside from the keel, some ribs, and the large Atlas-Imperial diesel engine. As this page notes, the vessel seems to have fire damage. It seems to be about 70-80ft in length, but estimation is difficult due to the condition of the wreck. Here is a photo of a similar (but larger) engine in another cannery tender.

The two photos above show the Highwater Island wreck. There is even less remaining than at the other site. You can still find some cylindrical tanks and the rudder, a few wood and metal bits showing the rough outline of the hull, and a few interior items like plates and glassware. This one seems shorter than the other wreck, maybe 50-60ft, but again, estimation is difficult.

The hollow steel boiler from the Highwater Island wreck appears to have floated across to a small peninsula known locally as “The Point”, where it rests at extreme-tide level slowly rusting away.

The propeller from this wreck was also removed by a prior resident of my family’s property, and dropped in the front yard. The story goes that the person believed it was brass, and planned to sell it for scrap, but when they began cutting into it, they realized it was cast iron. You can still see a cut section on one of the flukes.

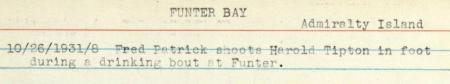

Is one of these wrecks the Anna Barron? I found a small snippet from a 1931 Google document claiming the Anna Barron sank at Point Couverden across Icy Strait, still with its original steam engines. Unfortunately the full text is not available.

“The “Anna Barron”, owned by the Alaska Pacific Salmon Corporation, believed to be the last remaining steam tender in the fleet, struck a rock and sank in Icy Strait July 22. Built many years ago by the former Thlinket Packing company, she was still valued at about $20,000 …”

This page contains some additional information, sourced from US Customs wreck reports. According to the report, The wood steam tender Anna Barron hit the rocks at Ansley Point (Near Point Couverden) after departing Funter Bay the night of Tuesday, July 22 1930. Captain George D. Black was carrying a half scow load of fish and was attempting to offload to scows tied to a dolphin (piling structure) between two reefs off Port Ansley (now known as Swanson Harbor). The wind and tide in the narrow passage proved too much for the vessel, and it was forced onto the rocks in the darkness while maneuvering to reach the dolphin. The captain was quoted as saying the Anna Barron might be raised in the future.

Some of the dolphins and other pilings are still visible in Swanson Harbor, and appear on nautical charts of the area.

In addition to the Anna Barron, the cannery also owned a 75′ boat named the Barron F. (From UW Freshwater and Marine Image Bank)

According to McCurdy there was an 85′ cannery tender named the Barron F built in 1917 for the Nooksack Packing Co. The US Merchant Vessel Registry lists a 65′ Barron F built in 1917, registry number 214967. I am not sure if these are all the same boat with errors in the published length, or different boats. It seems unlikely there would be so many vessels named after the Barron family in exactly the same way at the same time.

The cannery also seems to have owned a 53′ gas boat named the Buster, registry number 14481, built in 1889 in San Francisco. This boat caught fire and sank in Funter Bay in July of 1926, as mentioned here. The boat had left the cannery dock and suffered engine trouble, then a fire broke out in the gas engine during repairs. The vessel was assisted by the Anna Barron and the Driva (a 56ft gas towboat belonging to Juneau Lumber Mills), and towed to a dolphin. The mooring line burned and the boat drifted around the bay, burning all night, before sinking “in deep water”. I do not know where this wreck is located precisely. The cannery had just been purchased by the Sunny Point Packing Company in this year.

The Buster was probably either named after J.T. Barron himself (who sports the Nickname “Buster” scrawled on a portrait printed in the 1906 Pacific Fishermen Annual Review), or his son Robert, who was the model for the company’s “Buster Brand” logo. Robert was also featured on the cover of the May 1907 issue of Pacific Fisherman.

As mentioned previously, Robert died in 1917 while trying to save fellow airmen from an accident in Philadelphia. Mount Robert Barron in Funter Bay was named for him.

Robert also appears to have had a cannery boat named after him, the Robert Barron, a 44ft gas vessel built in 1901 (perhaps for J.T. Barron’s earlier cannery near Wrangell), registry 111335.

So, back to the wrecks on the beaches. Which boats are they? Digging through alaskashipwreck.com I find the following listed for Funter Bay:

Vernia, 6 ton 28ft sloop, blown onto a rock at or near the Kitten islands and sank in Lynn Canal Jan 4 1904. Cargo of fish and gear worth $200, boat worth $150. No casualties, but the boat was a total loss. Master was William Beckler of Juneau.

This one is interesting because it was listed as built at Funter Bay in 1919. The 38ft gas screw Sandy, owned by LF Morris of Juneau, caught fire and sank in Auke Bay in 1928, while carrying an illicit cargo of liquor in kegs. All but 6 kegs were destroyed, the rest were confiscated by prohibition officers.

Tiny Boy, 46ft wooden oil (diesel) freighter owned by WH Bowman sank near Funter Bay Oct 11, 1940. All 6 crewmen escaped.

Reliance No 3, a 32ft wooden fishing vessel owned by WJ Smith, burned and sank off Naked Island near Funter Bay in 1953.

Morzhovoi, an 80ft wooden oil screw (diesel) boat, burned in Funter Bay on June 10, 1955. Reported as having a 165hp engine, being built in Seattle in 1917, and being used for freight service. Owned by the PE Harris Company, registry 214789.

PE Harris (which later became Peter Pan seafoods) purchased the Funter Bay cannery from the Sunny Point Packing Co around 1941. Morzohovoi Bay was another location where PE Harris co owned a cannery.

The Morzhovoi seems like the best candidate for the Coot Cove wreck. Digging some more, I find a reference in McCurdy to Morzhovoi; 80ft, 110hp, first vessel built at the National Shipbuilding Co yard in Seattle. Built for the Sockeye Salmon Co of Morzohovoi Bay (who later leased their cannery to PE Harris)

The 1918 Merchant Vessels of the United States registry lists the following specs for the Morzhovoi: 81 tons, 80.2ft long, 18.9ft breadth, 7.6ft depth, Fish service, crew of 7, 110hp gas engine, home port Seattle. Its registry number appears on the rolls of merchant vessels until 1956, when it disappears. In the 1955 registry it’s listed as an Oil boat of 165hp, radio call sign WB4935, belonging to PE Harris of Juneau.

Here’s a photo of the Morzhovoi from the 1919 issue of Pacific Motorboat. It lists some slightly inconsistent info (original HP and owner are correct, but year and length are off. I would suspect that these are typos).

Obviously the 110hp Frisco gas engine must have been replaced with a 165hp Atlas-Imperial diesel during a later refit.

So there’s one wreck identified to a high probability!

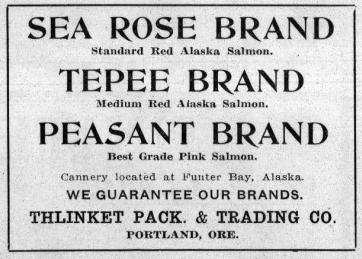

Trolling (pun intended) through the merchant vessel registry, I find a few other boats which may have been associated with the Funter Bay cannery. In the mid 1920s these include the Peasant, a 46ft gas boat built in 1926, registry 225554 and the Tepee, a 29′ gas boat, registry 210208 (The Thlinket Packing Co had canned salmon brands called “Peasant” and “Tepee”).

While researching Funter Bay ships, I was surprised to learn that the Thlinket Packing Co owned a large sailing vessel, the General Fairchild. This clipper ship seems to have been converted into a cannery barge, hauling packaged product from the canneries to sales “Down South”. It appears to have been used at the “Shilkat” (Chilkat?) cannery, probably near Haines, but may have also served Funter Bay. The ship was taken out of service after only two years, and then sold to another company.

Prior to starting the Funter Bay cannery in 1902, the Thlinket Packing Co seems to have been active in Southern Southeast Alaska, using a leased steamer named the Baranoff and a 6 ton launch (gas boat) named the Perhaps, (per this article). The company (and later owners) also owned a number of other boats, used throughout Alaska, to the point where a complete list would take quite a bit of time to produce and would take this post wandering even further through Southeast maritime history! None of this helps me identify the other wreck at this time, but maybe I’ll find something as I continue digging.

Moving along to other shipwrecks around the bay…

The Funter Bay Cannery also had a number of scows, which were fairly standard among canneries of that era. These were basically open wooden-hulled barges with high sideboards, used to transport fish in bulk from the traps to the cannery. Some of these were also registered with the government, and had such imaginitive names as “Scow #1”, etc.

They were simple, rugged vessels which could be beached for storage over the winter. Scow Bay (AKA Coot Cove), around the corner from the main cannery dock, held the slipways and drydocks for scow storage. There are a number of scows still resting there, decaying into the rainforest.

Scows on the drydocks at Scow Bay.

Some of the scows had their own machinery on board, including what looks like a small steam engine. There was another steam engine in the woods that ran a winch for hauling the scows up wooden ramps (slipways) to their storage spot.

Port names listed on the side of a scow. Visible are “Seattle” and “Juneau”.

Slipways at Scow Bay.

Scow Bay also has the remains of a ~30ft fishing boat:

Wrecked fishing boats can be found in a few places around Funter Bay.

The Jolene M, a fishing boat which drug anchor and hit Highwater Island one night when I was young. The owner re-floated it and attempted to beach it for repairs, but never managed to get very much done with it. This is an old picture, there’s little visible of the wreck today aside from some metal bits in the mud at low tide.

The Jolene M looks more like this now. Wood decays very fast in tidal environments.

The Nimrod, a wooden boat (probably also a fishing boat) which was beached up “Nimrod Creek” (local name). There is also quite a bit less of this boat remaining intact today. (Update 4/23/13: This was originally a tugboat, I’ll add more details in a future post).

More recent Nimrod photo.

And just for fun, here are a few even smaller abandoned boats (skiffs). Maybe some of them are the lifeboats seen on the cannery tenders, or the small sailing boats mentioned in articles about the Barron family? Or they could simply be some of the many small skiffs that you find in any Southeast Alaska community, as common as the family cars down south.

Once again I have produced a stream of meandering research beyond all reason. And I still have plenty more to expand on things mentioned in this post… what happened to the Barron Family? How did they use legal loopholes to get their land? What was the later cannery history? What other fishing-related activities happened around the bay? Just a few things I hope to cover in the future!

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts