The Thlinket Packing Co at Funter Bay employed a number of different people over the years in a variety of positions. Below is a partial list, gleaned from early 20th century newspapers. Keep in mind that consistent spelling of names in the early 1900s was somewhat optional!

_____________________________________________________________

James T. Barron – Owner and Manager, 1902 – ~1926. More on the Barron family here.

_____________________________________________________________

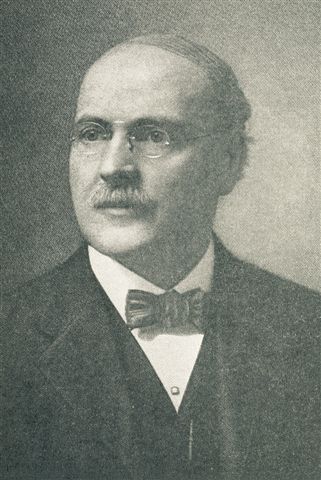

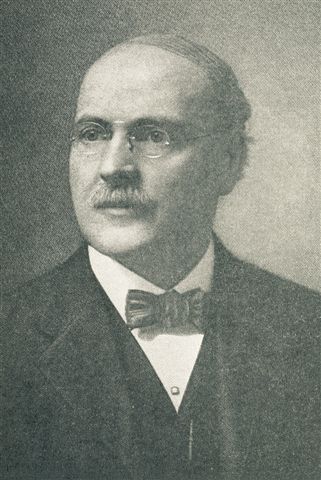

Judge Michael George “MG” Munly (1854-1923)

The family name was originally spelled “Munley”, but Michael later dropped the E. He was company Secretary and brother-in-law to James Barron. He married Mary Nixon, sister of James Barron’s wife Elizabeth. Munly was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar in 1882. He was deputy city attorney in Portland, and was appointed a judge of the Oregon circuit court from 1892-1894. Munly ran unsuccesfuly for mayor of Portland in 1909. Along with the Barron family, Munley and family were frequent visitors to the Funter Bay cannery.

Judge Munly’s grave and additional information.

1922 Biography of M. G. Munly

1928 Biography

_____________________________________________________________

C. F. Whitney was Sales Manager at the company, based in the Portland office. He seems to have rarely visited the Funter Bay operation. Prior to taking this position, Whitney had been sales manager of the New York Life Insurance Co.

_____________________________________________________________

Mr. and Mrs. Norton – Listed as winter caretakers at the cannery in 1903. Left in February to develop some timber claims in Oregon.

_____________________________________________________________

James Lawlor – (Sometimes spelled Lawler) was caretaker and winter foreman(?) from at least 1903-1909. He took over from the Norton’s in Feb 1903 and began preparations for the upcoming coming packing season.

_____________________________________________________________

Chris Houger (Sometimes spelled Hooger, Hugher, Hager, etc) was “Outside Foreman” at the Funter Bay cannery from at least 1903-1919. ?He was in charge of piling crews, trap installations, nets, etc. His wife was noted as being the cannery’s bookkeeper in 1914. In 1917 Western Canner and Packer referred to him as Manager of the Thlinket Packing Co.

_____________________________________________________________

Captain Haly of the Rainier – hired to bring up the “fishing steamer Barron” from the South for the 1903 season.

_____________________________________________________________

Mr. and Mrs. A. C. Bogarth – Operated fish traps near the Funter Bay cannery for several years around 1903.

_____________________________________________________________

Captain Crockett – skippered the Anna Baron during at least the 1904-1907 seasons.

_____________________________________________________________

Captain Mason was listed as skippering the Anna Barron in 1911.

_____________________________________________________________

Captain Martin Holdst (Also listed as Martin Olson) of the Belle was employed in the winter of 1909-1910 repairing the water and power systems at the cannery.

_____________________________________________________________

Pat. F. Mulvaney was the storekeeper at the Funter Bay cannery from at least 1909-1917 and listed as watchman in 1918 -1919.

_____________________________________________________________

Fred Barker (Or T. H. Barker) was listed as cannery superintendent in 1911. His brother “Billy” Barker was the assayer at the Perseverance mine.

_____________________________________________________________

Cannery employees listed as arriving in spring of 1911 were: H. H. Harvey, C. W. Young, G. W. Scott, E. A. Harriman, Thos. Redwood, F. Phelps, W. F. Brillian and H. Wills.

_____________________________________________________________

A. M. “Bob” Bell was listed as a canneryman at Funter Bay in 1912. There is also an A. E. L. Bell mentioned, and possibly another Bell who ran the Glacier cannery.

_____________________________________________________________

F. Hilder was an employee at the cannery in 1914.

_____________________________________________________________

George W. (or L.) Bowman was listed as cannery superintendent in 1914. He formerly worked for the Northwestern Fisheries company.

_____________________________________________________________

J. F. Bennett was listed as a cannery employee in 1915, his arm was caught in a rotating shaft in June and he required skin grafts at the Juneau hospital.

_____________________________________________________________

Harold W. Chutter (Or Chuttes or Chutte or Shutter or Chutler) is listed as the “popular superintendent of the Funter Bay Canning Co” in 1916 and 1917. In Feb. 1917 it was reported that “Mrs. Chutter, formerly of Funter Bay” had left to marry the former accountant for the Juneau Electric Light company. In December of 1917 it was reported that Chutter was closing up his affairs at the cannery and leaving for Bremerton to join the Navy. Sales Manager Whitney planned to come North from Portland to temporarily fill in as manager.

_____________________________________________________________

C.L. Cook is listed as bookkeeper in 1917.

_____________________________________________________________

G.C. Coffin, an employee of the cannery, was at the Juneau hospital in 1917 for eye treatment.

_____________________________________________________________

E. W. Hopper is described as the superintendent and/or manager of the cannery in 1918. His wife and daughter also resided at Funter in the summers.

_____________________________________________________________

Capt. John Maurstad skippered the Barron F. in 1918. According to the Kinky Bayers notes, he came to Alaska in 1909 and was a resident of Angoon. He did some logging and built a sawmill and Kasnaku Bay (Hidden Falls) in 1927. In 1940 he was in charge of a CCC crew building roads near Angoon. He may have died around 1942 at age 53.

_____________________________________________________________

D. J. Wynkoop, formerly of the Treadwell mine, was employed at the cannery in 1918.

_____________________________________________________________

Captain A. Woods is listed as running the Anna Barron in 1918. He fell from a 20ft ladder in February and was in St. Ann’s hospital expected to fully recover.

_____________________________________________________________

Chinese, Filipino, and Native Alaskan employees were usually only mentioned in passing, with no names given. A 1914 article lists the following “strange names” of Chinese workers bound for Funter Bay, but states that the purser of the steamship City of Seattle may have been kidding around: “Ten Pin, Hinge Lock, Wong Toon, Mop Dip, Wong Chuck, and Sam Lea“.

I’ve tried briefly looking into each of these people, but have not found any detail on most of them. I may try to come back to this post if more information becomes available. If you know anything about any of them, please feel free to contact me!

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts