Travel and shipping to Funter Bay in the late 19th and early 20th century required owning a boat, hitching a ride on a boat, or paying for passage on one of the occasional commercial vessels to stop at the bay.

Below is a ticket stub from 1928. Funter Bay is listed as one of many possible destinations, including various small towns, lighthouses, canneries, fox farms, mines, etc. Fare in 1928 from Juneau to Funter was $5.50.

Freight service was irregular, arriving whenever there was a large load of something (lumber, machinery, workers, etc) to deliver. This is the case today as well, freight is often brought in companies such as John Gitkov’s Southeast Alaska Lighterage, using rebuilt military landing craft. Households at Funter Bay would often go together on a load once or twice a year, including fuel, building materials, ATVs, etc.

Freight delivery at Funter Bay in the 1990s:

During the industrial years of canning and mining, Funter Bay had semi-regular mail service (at least during the summer). Cannery owner J.T. Barron occasionally served as Fourth Class Postmaster, although when the cannery started in 1902, James Largan is listed as Postmaster. In 1921, William N Williams is listed as Postmaster. Commonly the storekeeper in a small town would hold this position on the side, although it also included several hundred dollars a year in government salary and sometimes kept very small stores in the black. Although the Rural Free Delivery service eliminated many 4th-class postmaster positions, they persisted in Alaska for some time (Harold Hargrave was Postmaster at Funter Bay in 1954).

Here’s a photo of the Funter Bay post office (date unknown).

From the early 1920s to late 1940s, mail was delivered by chartered vessels such as the Estebeth (sometimes spelled Estabeth), a 55ft wood diesel boat which made semi-regular mail and passenger runs all over Southeast Alaska. The boat was owned by the Davis Transportation Co under captain James V Davis (who later organized Marine Airways and served as a state legislator).

The Estebeth at Sitka, courtesy of Jim Dangel, used with permission:

Above ad from the 1920 Issue of Pacific Motorboat. In 1920 the Estebeth had a crew of 3.

A few more photos of the Estebeth.

The Estebeth (Reg # 216559) is indeed listed in 1920 as having an 80hp gas engine, but despite the “Reliability of Frisco Standard Gas engines” described above, the boat is listed in 1925 as having switched to a 90hp diesel engine. By 1945 the boat had upgraded to a 100hp diesel, added a radio (call sign WNOL) , and had a crew of 5.

According to various wreck reports, the Estebeth either went aground near Swanson Harbor, or burned near Point Couverden on March 31, 1948. A local resident recalls that the Estabeth burned in Crab Cove at Funter Bay. I’m trying to verify which was which. Either way, this was not the first accident the boat had suffered, BOEM Shipwreck lists mention that she hit a shoal near Kosciusko island in 1927, stranded twice in 1929 at Zimovia Strait and Port Alexander, and scraped a rock in Tabenkof Bay in 1929 (I wonder if they fired the 1929 crew!). The boat is also mentioned in various history texts as being present to rescue various stranded mariners and assist disabled vessels all over Southeast.

Another vessel used for mail and freight service in Southeast Alaska was the Margnita, operated by the Coastwise Transportation Co of Alaska (there was also a Coastwise Transportation Co of Maine). The Margnita was an 83ft boat built in 1926, with a 200hp gas engine and a crew of 8. The boat was sold in 1931 and renamed the Polar Bear, and the Coastwise Transportation Co of Alaska seems to have vanished, one record mentions that captain H.M. Peterson was arrested for fraud relating to some mining claims in the Nome area, and an article mentions that the vessel sat idle for several years before being purchased by the Kodiak Guides Association.

“WOLD COMMANDS “POLAR BEAR” Capt. Peter Wold… in August assumed command of the yacht “Polar Bear“. This vessel, as the “Margnita”, was long well known as a passenger and freight boat in Alaska waters.” (From Pacific Fisherman Journal, 1931)

The Polar Bear sank near Kodiak in 1935, and was raised for salvage by divers in 1937.

(From New York Post, July 20 1935)

Another mail boat serving the area after the 1940s was the Forester, (Reg 209556). Owned by Lloyd “Kinky” Bayers and later by James Colo, the Forester was a 63′ boat built in 1912 in Seattle. In 1945 it had a 60hp diesel engine and a crew of 2. By 1965 it was listed as having a 200hp diesel and owned by John Gallagher. The vessel was still active as of 1989, owned by Bluewater Farms, a fish farm in Port Townsend. It is no longer listed as an active vessel with the USCG.

By the 1930s, reliable aircraft service began supplementing mail boats (although there was still mail boat service through the ’70s for larger items). In the 1980s – early 2000s, Funter Bay had weekly year-round mail delivery by seaplane, paid for by a federal mail contract. Ward Air of Juneau, known for their safety and punctuality, had a long-running contract for mail delivery. Ward Air was much more dependable than the Postal Service itself, the feds were constantly trying to cut service to small towns, and at various times Funter Bay’s “delivery location” included a box under someone’s desk at the Juneau post office, which would get dumped at Ward Air if and when the post office happened to remember. We also frequently got mail for other small Southeast towns, as they got our mail. It was usually a good bet that anything mailed or mail-ordered would be a few weeks or a month to show up (next-day and two-day letter delivery in the Lower 48 still weirds me out).

Much of rural Alaska shared the 5-digit 99850, Funter Bay’s full zip code was 99850-0140.

The mail box at Funter Bay. Mail came once a week via seaplane when I was growing up.

As mentioned in a previous post, the number and variety of commercial vessels calling at Funter Bay would make for a very extensive list. Further confusing the issue is that many of the shipping companies mentioned here were merged, consolidated, or otherwise interwoven to some extent during the mid 20th century. I’ll try to document a few that I’ve been able to find references to.

In 1904, Funter Bay was designated by the US Treasury Dept. as a “Special Landing Place” for vessels to be under the supervision of a customs inspector. This was “for landing coal, salt, railroad iron, and other like articles in bulk”.

Steamship service was on the flag stop principle. Steamers regularly passed Funter Bay on the way to and from Juneau and Skagway, and companies could request that a ship make a stop at Funter along the way. Irregular stops like Funter were not listed on the larger companies’ official route maps and were not typically factored into the printed timetables, although an 1896 timetable from the Pacific Steamship Co notes that

“These dates so far as they relate to ports in Alaska, are purely approximate. In case of steamers calling at other ports (which they are liable to) or in case of fogs or other unfavorable weather, tides, etc, these dates cannot be relied on. “

Alaska Steamship Co route map, 1936. Funter Bay is visible just to the SW of Juneau:

A reference in Barry Roderick’s Preliminary History of Admiralty Island mentions the Steamer Al-Ki delivering materials and workmen to Funter Bay in 1895. There were several vessels with this name in the Pacific Northwest, but I believe this was the 200ft steamship out of San Francisco which called at many small towns, mines, and canneries in Southeast Alaska. The Al-Ki was wrecked at Point Agusta in 1917. More information on the wreck is available here (scroll down).

The Admiral Goodrich is listed as delivering sawmill equipment to Funter in 1918. This was a cargo vessel owned by the Pacific Steamship Company. Formerly the SS Aroline, and later the Noyo, this ship was wrecked at Point Arena, CA in 1935.

Admiral Goodrich in 1918:

The vessel Driva, owned by Juneau Lumber mills (and previously mentioned as assisting the burning Buster at Funter Bay in 1926) occasionally called at Funter to deliver lumber for construction (and possibly to pick up cut logs). Driva was a 56ft gas towboat. It seems to have been wrecked near Douglas Island sometime between 1935 (when it is listed in the Merchant Vessel Registry) and 1937, when the wreck was photographed.

Juneau Lumber Mills also had a vessel called the Virginia IV. Here’s a photo of it at the dock in Juneau, along with the ferry Teddy, probably the same Teddy which was reported abandoned at Funter Bay in 1959. The Virginia IV is seen on the right in the above link, in it was a 97′ boat built in Tacoma in 1904 as the steam vessel Tyrus, registry 200681. By the 1920s it had a diesel engine and had additional superstructure added aft of the wheelhouse.

The 1905 book “A Trip to Alaska” mentions the Steamship Cottage City (233ft long, built 1890) stopping at Funter Bay on the way north to deliver salt for the cannery (described in the book as the largest in Alaska), and then again on the southbound trip to pick up six thousand cases of canned salmon (each case holding 48 2-pound cans).

More information on the Cottage City. and what became of the ship.

A 1915 issue of The Timberman magazine reports the steamship City of Seattle bound for Funter Bay with a cargo of 3,000 wood shingles.

More on the City of Seattle.

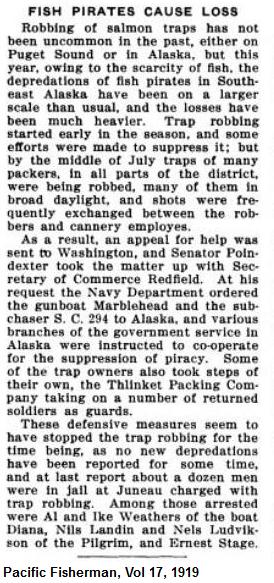

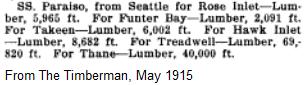

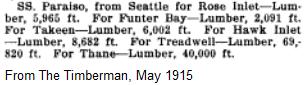

And another 1915 sailing mentioned in the Timberman is the freighter SS Paraiso:

The Paraiso was later used by the US Navy and renamed the USS Malanao.

A 1917 issue of Western Canner and Packer reported that the steamer Admiral Watson arrived in Seattle with 40,000 cases of salmon from various canneries, including Funter Bay.

While the Admiral Watson occasionally ran aground, or even sank, (it was rammed by the Paraiso) it survived into the 1930s when it was sold to Japanese scrappers.

The Admiral Rogers visited Funter several times. In 1925, filling in for the Ruth Alexander, which had originally been scheduled. Both were ships of the Pacific Steamship Co / Admiral Line. The Rogers was formerly known as the SS Spokane.

I have this photo floating around my hard drive with the note “SS Spokane at Funter Bay, 1905″. I’m not sure where it came from:

More info on the Admiral Rogers (scroll down or search).

Here’s a menu from the Admiral Rodgers from that same year.

The Ruth Alexander:

The SS Cordova was another Pacific Steamship Co / Alaska Steamship Co vessel to visit Funter Bay. Here is an excellent website about another small town where the Cordova regularly called.

Photo of the SS Cordova by the Helsel Photo Co of Kodiak, courtesy of tanignak.com:

The Nelson Steamship Co of San Francisco owned a 298ft freight steamer named the Jacox, based out of Portland OR. This vessel dropped off supplies and materials at Funter Bay.

I believe this is the same Jacox, which also saw service across the Pacific to Asia and Australia:

It seems odd today to think of such large steamships calling at Funter Bay. The largest vessels we usually saw in the bay were yachts and the occasional research vessel, the present-day docks are more suited for small fishing boats and cruisers. I have heard that some of these larger steamships used the cannery dock to discharge freight; probably the wharf on which cannery buildings were constructed out over the bay. It’s also possible that they would lower freight into barges or scows to be taken ashore to operations lacking a dock (like the Dano mine). I’ve also heard from recreational divers that such steamships would sometimes have lazy kitchen crews, who would throw dirty plates out the window instead of washing them. The intact china plates being recovered from under the cannery dock by these divers certainly seems to support that story!

And while we’re at it, here are a few more Funter Bay shipwrecks I’ve come across (I should try to make a comprehensive list of these!)

10:22/1928: The Anna Helen, a gas yacht used as a floating dental office, burned after an engine backfire caused a gasoline explosion. Vessel sank 2 miles from entrance to Funter Bay.

10/14/1938: An unnamed troller belonging to Geo. Ford was found sunk in Funter Bay, with no sign of him around. Fred Patrick was also missing. Both were found at Funter three days later (From Juneau newspaper via Kinky Bayers note cards). (I was able to devote an entire post to the adventures of Fred Patrick).

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts