This began as a dry discussion of trap types, and ended up with gun fights, legal battles, piracy, and everything else that goes with Alaskan fishing!

As mentioned before, the Funter Bay cannery operated mainly with fish traps (vs fishing boats). These traps were designed to intercept salmon as they returned to spawning streams, penning them in large fixed nets until they could be scooped out.

There were two types of fish trap used in the Funter Bay area. “Pound Nets” hung from fixed pilings driven into the sea bottom. Many of these pilings had to be replaced each season, as the winter storms would knock them loose. “Floating Traps” had nets hung from a latticework of floating logs, and were used in deeper water or locations with rocky bottoms. These traps were towed into protected coves for winter storage. Both types of trap would be located a few hundred feet offshore, with a “leader” strung towards the beach (and sometimes a “Jigger” extending seaward) to intercept passing salmon. This page has some more explanation and diagrams.

Pound Net:

Floating Trap:

These images show one of the Thlinket Packing Co’s pound-type traps near Funter Bay (Trap #7):

My first post on Funter Bay History shows Trap #6 at the Kittens (islands), also of the pound type.

Here is an example of a floating trap. The structure on top is the watchman’s shack:

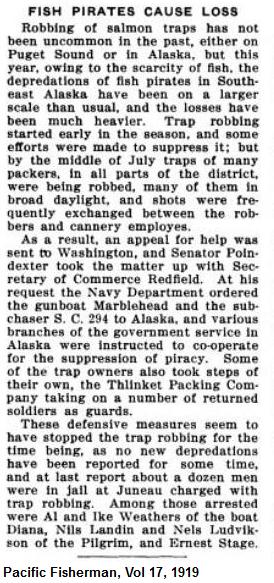

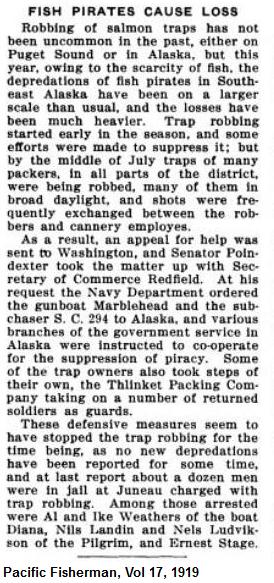

As mentioned, watchmen on the traps were an attempt to prevent trap robbing or “Fish Piracy” at remote traps, which was quite common. Independent fishermen hated traps, which they (correctly) felt were taking too many salmon. Many fishermen felt that fish in a trap were fair game, and that trap robbing did not “cost” anything to the trap owner. In fact, the pirates would often sell the stolen fish to the same company that owned the traps! The problem became so bad that the governor of Alaska dispatched surplus navy boats to combat pirates, and the Thlinket Packing Co hired WWI veterans to serve as armed guards.

In July of 1919, the Weathers brothers, Al and Ike, along with Ernest Stage, were charged with assault and attempted robbery in a fish piracy case. The trio were accused of using the gas boat Diana to attack Hoonah Packing co’s tender Forrester near Funter Bay. Captain Alfred Knutson testified that his boat came under fire by the trio. Thlinket Packing Co trap watchman Ted Likeness was a witness. Earnest Stage was initially arrested for stealing $10 worth of fish from Funter Bay. Al Weathers was found guilty and given 4 years in jail, with the jury recommending clemency due to his young age.

Info on the USS Marblehead.

Photo of a WWI sub chaser in Alaska.

Fish piracy was reduced by 1925 after several canning companies joined together to patrol the area.

“Fish piracy, or the robbery of fish traps, which in previous seasons was bitterly complained of by salmon canners in southeastern Alaska, was reduced to a minimum during the season of 1925. This was accomplished chiefly through the maintenance of a patrol organized by the larger canners and operated under the supervision of deputy United States marshals. A number of cruising boats were engaged in this patrol and covered waters in the vicinity of Icy Strait, Niblack, Street Island, Behm Canal, Kanagunut, Rose Inlet, Dall Head, Hidden Inlet, Union Bay, and the west coast of Prince of Wales Island.” From Bureau of Fisheries report, 1926.

Some more information on fish piracy can be found here (restoring a patrol boat), here (the story of a miner turned pirate), and here (mentioning the piratical family history of Ketchikan’s mayor).

In addition to battling pirates, salmon packing companies were also fiercely competitive with eachother, vying for the same salmon runs, the most desirable trap locations, and the best land for canneries. An extreme example of this was “trap jumping”, similar to the phenomenon of mine claim jumping where one prospector would steal the land or resources of another. More details shortly…

Pound net traps often had a watchman on shore, vs floating traps with their onboard housing. As I previously noted, the Thlinket Packing Co acquired land via the homestead act from which to base their traps (although the person filing for the homestead would usually not be the one living there!). I showed a survey of cannery owner J.T. Barron’s “homestead” in this post. Below is a survey of the “homestead” at a trap site south of Funter:

This homestead (located at Lizard Head point just South of Funter) was fairly openly a front for cannery development, being transferred very quickly to T.P.Co owner James Barron. Barron had previously held a lease from the Alaska Packers Association for a trap they installed in 1908 at Lizard Head, and was moving to acquire the shore and upland to support this site.

“…On or about the first day of March, A. D. 1911, for value received, the said V. A. Robertson conveyed by good and sufficient deed in writing the above-described tract, lot or parcel of land embraced within said U. S. Nonmineral Survey No. 804 aforesaid to James T. Barron.”

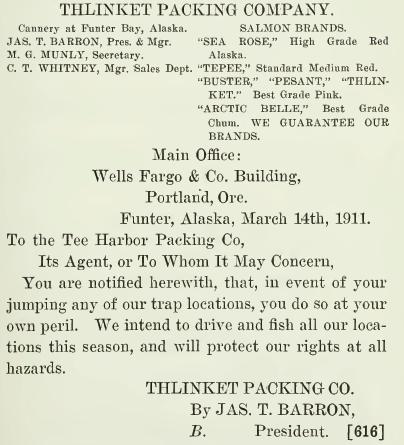

However, before the Thlinket Packing Co could finish building their trap, Clarence J. Alexander, AKA “Claire Alexander” of the Tee Harbor Packing Co swooped in and installed his own, thus “corking off” Barron. He had previously worked on the pile-driving crew for the Alaska Packers Association, and knew exactly where the trap should go. Alexander even used some of the pilings that Barron had already driven! Barron sued, and some of the court documents are online (part 1 and part 2).

Perhaps Mr. Alexander’s “opportunity” was when Barron left the state?:

Claire Alexander’s fish trap shown in front of Barron’s Lizard Head property, from court documents:

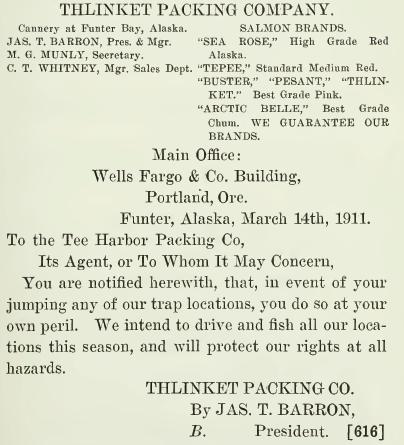

Barron’s initial letter to Alexander:

In the court case, Barron testified not that he planned a trap (as indicated by his letter and other testimony), but that he wanted to use the site as a temporary mooring for boats. He mentioned that it was too hard to tow loaded scows to Funter Bay against a North wind. He complains that Alexander’s trap blocks his water access. Alexander claimed he had no knowledge of Barron’s so-called homestead and didn’t notice any development at the site (despite incorporating Barron’s pilings into his trap). The court found against Barron and ruled that Alexander’s trap did not block Barron’s access to his property.

Some 1911 photos from the Lizard Head trap site, including the beginnings of the T.P. Co. watchman’s cabin:

Claire Alexander would go on to found the Hoonah Packing Co a few years later, and his trap at Lizard Head was still in place, in the same configuration, in 1948.

Laws regarding fish traps tended to fluctuate. Traps were originally fairly unregulated, and canneries would often place them directly in stream mouths, intercepting the entire spawning population until the “run” of salmon was destroyed. Later regulations placed limits on where traps could be located, when they could operate, how long the jiggers could be, etc. By the 1940s, the salmon population had declined so much that trap catches were fairly low, but the price of salmon had risen enough to keep traps cost-effective. When Alaska became a state in 1959, traps were outlawed entirely, leading to the closure of many canneries (other methods of fishing were not efficient enough for the size and type of these operations).

The Thlinket Packing Co (and later owners of the cannery) occasionally ran afoul of fish and game regulations.

“During the season of 1926, four salmon traps were seized in south-eastern Alaska for illegal fishing during the weekly closed period. … A trap of P. E. Harris & Co., near Hawk Inlet, and one of the Alaska Pacific Fisheries, near Funter Bay. were seized on July 11. On trial the watchmen were found not guilty, but the traps were still in the custody of the United States marshal at the end of the season.” Bureau of Fisheries report, 1927.

I came across a set of 1948 aerial photos of Funter Bay while looking for another map (from http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). The original is linked in my post on Funter Bay maps, below are a few excerpts showing fish traps around the bay in 1948.

A trap outside the south shore of Funter Bay (possibly pound net trap #7) Note the wake of the boat, possibly a cannery tender, leaving the trap:

C.J Alexander’s pound net style trap at Lizard Head in 1948, looking a little worse for wear. The trap has the same approximate layout as shown in the 1911 diagram (inset), but the line of pilings for the lead going to shore has vanished.

A number of traps seem to have been abandoned by the Thlinket Packing Co at this point. There is no sign of Trap #6 at the Kittens in the 1948 aerials. Several of the floating-style traps are also sitting on the beach or drawn up in shallow coves where they would go dry at low tide. More traps are visible operating and in place along the shore between Funter and Hawk Inlet, but I’m not sure which companies were operating these.

Fish trap on the beach in Crab Cove:

Crab Cove trap logs outlined to be more visible:

You can see the shadow of the watchman’s shack, this might have been the shack that became the entry of our house, as mentioned in an earlier post. Our neighbor Harvey Smith also had a few sheds that were the right size to be trap watchman’s shacks, I might detail those later on.

Floating trap in place along the Admiralty Island shore south of Funter Bay, with buoyed lead net going to shore:

Down at the other end of the bay, we can see a jumble of pickup sticks on the estuary between Ottesen and Dano creeks, near the sandy beach. A few hints of the outline of a trap are visible, this might be one or more damaged or disintegrating traps:

Here is the cannery site and Scow Bay with the scows visible on slipways:

And finally, back to the present day: here’s a trap log washed up at the sandy beach, probably from one of the traps seen above. You can see various bolts and hardware that connected the trap logs together:

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts