As mentioned once or twice before, my Dad, Phil Emerson, began hand trolling in Southeast Alaska in the early 1970s, after building a small boat at Funter Bay. Donna, my Mom, fished with him for a few years (he had upgraded to a larger boat by then). Dad’s uncle Robert Emerson also lived at Funter Bay and fished for many years, as did his son Joe. Dr. Joe Riederer also fished around Funter and built a cabin there when I was younger. Our Neighbor Joe Giefer also trolled.

Compiling a full list of people who fished commercially in and around Funter Bay over the past decades is likely impossible, but there are a few fishermen I’ve been able to find reference to. One great source are the notecards left by Captain Lloyd “Kinky” Bayers. His extensive material on SE Alaska marine history fills multiple collections at the Alaska State Library, some of them can be found here. My parents also provided some of the information, passed on from other residents of Funter Bay at the time they moved there. The Merchant Vessel registration lists are again helpful in determining vessel and ownership details.

Funter Bay serves as a convenient harbor for fishing the junction of Lynn Canal, Chatham Strait, and Stevens Passage. Geologist John Mertie reported around 1919 that Funter Bay was a busy harbor where many fishing boats took refuge during the sudden gales and heavy fogs characteristic of the area. Capt. Bayers himself took shelter at Funter on occasion while working on the Estabeth and later while running the mail boat Forester. Hand trollers who fished from small open boats in the summer would often stay in tents or small cabins on the beach in Funter Bay. Those with larger boats would live on board, anchoring or tying to one of the docks during bad weather.

Salmon troller at Funter around 1920 (Winter & Pond):

Some of the people listed below lived at Funter permanently. Some may have been part time or summer residents, and some may have merely passed through. Hand trollers are especially hard to find, because their small boats often had only numbers like T-105, rather than names, and did not have commerce dept. registry numbers. I have provided what details I can find.

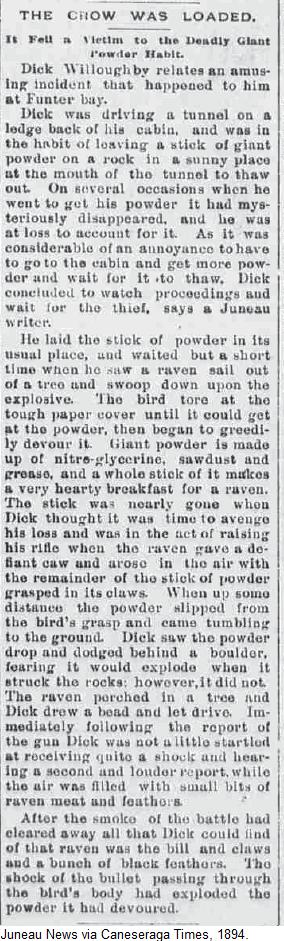

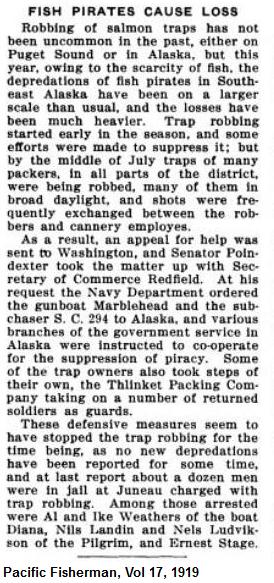

Alvin Weathers fished around Funter before 1920 and through the mid 1930s. I believe this was the same Al Weathers I previously mentioned, who was arrested for fish piracy with his brother Ike Weathers in 1919.

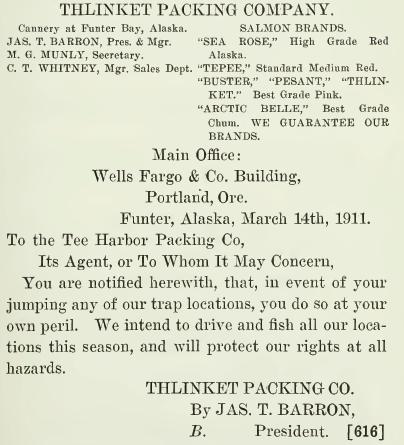

The “Weathers Boys” came to work in the Treadwell mines around 1915, and a 1916 article in the Daily Alaska Dispatch mentioned that they were looking for an island to homestead and trap. They seem to have turned to piracy soon afterward. In July of 1918 Al and Ike were charged with robbing a trap south of Point Retreat. The trap watchman, F.C. Wright, was accused of aiding them, but was cleared. The brothers managed to get off that time due to lack of evidence. After being convicted of the July 1919 cannery tender attack, Al and Ike were sentenced to 4 years in Washington state. Their boat in 1919 was the 37′ Diana, it was purchased by Chas Goldstein after their conviction. Ironically, by September the Diana was being used as a cannery tender.

In 1934, Al had the 32ft vessel Ace. In 1935 he bought the Al Jr, a brand new (built 1935) 40′ fishing boat with a 35hp diesel and a crew of 3 (per Merchant Vessel registry). Al may have owned a house on Fritz Cove Rd around 1935.

Another local fisherman and occasional fish pirate was “Humpy Nils” Landin, who had the 41ft vessel North Shore in 1935, fishing between Juneau and Hoonah. He and Nels Ludvigson of the vessel Pilgrim were sent before a grand jury for fish piracy in July of 1919.

The trial transcripts and appeals court documents from some of these cases are a wealth of information. In a 1920 appeals case, the US attorney cross-examines O.E. Bennett, a local fish buyer accused of aiding pirates. Bennett admitted that he had moored his fish buying scow at “Pirate Cove” near Swanson Harbor, but denied that he was specifically buying from pirate boats or that he knew which boats were pirates. Some of the commonly known pirate boats listed by the attorney were; The Diana, the Thalia, the Juneau, the May, and the Pilgrim.

Kinky Bayers’ notes mention many other names of pirates operating in the Juneau area, as late as 1940. Much of the information implies that convictions were hard to get, except in extreme cases like the Weathers’ where shots were fired at cannery personnel. He mentions that in 1924, at least 30 boats were known to be pirates, and multiple canneries had agreed not to buy fish from any of them.

In September of 1919 a 40′ gas boat named Sandy sank in Juneau, the owner was reported to be at Funter Bay (As previously mentioned, there was another Sandy built at Funter in 1919, which also sank in Juneau while smuggling moonshine in 1928). One of these may have been a fishing boat.

In October of 1924, Peter Hobson of the Myrtle pulled two trollers off the rocks outside Funter Bay; The Skip Jack, with Matsu Samato, his wife and 5 children, and the T-115, with two unnamed men. Damage to the boats was minor.

J. Kikuchi, a Japanese fisherman, was reported missing and feared drowned in July 1926, after his troller was found circling aimlessly off Funter Bay and towed in by other fishermen.

In December of 1927, many Juneau boats were reported storm-bound at Funter for 9 days, including the Pacific and the Alpha. The T-203, also known as the Buster, drifted into Funter Bay with owner A. Waara missing. (A different Buster than the cannery tender which sank the previous year at Funter).

The troller Gloria (probably a 39′ boat from Sitka) was operating around Funter Bay in 1928, when the crew rescued Dr. W.F. Good of the Anna Helen (a traveling dentist’s office, which caught fire outside the bay).

Emil Samuelson of the halibut boat Dixon operated around Funter Bay. He rescued the crew of the cannery tender Anna Barron when she sank at Point Couverden in 1930, and brought them back to Funter Bay.

Fred Patrick of the vessel Fearless lived in Funter Bay in the 1930s. He was a fairly unlucky fellow.

Harold Tipton may have been a Funter Bay fisherman, he has the distinction of being shot in the foot by Fred Patrick in 1931. He may be the same person mentioned here.

“Funter Bay Pete” (Pete Brynoff or Brynolf), owned the troller T-3802. In August of 1934 his boat broke down off Rocky Island, and Al Weathers towed him to Swanson Harbor. In the 1940 census there is a 72 year old Peter Brynolf listed as living at Fritz Cove Rd in Juneau, born about 1868 in Sweeden. He died in 1943.

The Fremont was listed as fishing around Funter Bay in the winter of 1936.

Geo Ford had a troller which sank at Funter Bay in 1938.

A.F. Bixby homesteaded at Funter Bay in the 1930s. This may have been Al F. Bixby whose family is mentioned in the Bayers notecards, his wife died in July of 1939. I am not sure if they fished or not.

Hal Hibbs lived at Funter Bay in the 1940s, and owned the F/V Mary Ann.

Elmer P Loose who owned the Nimrod and the Sally Ann, lived at Funter in the 1960s.

Ray Martin fished out of Funter Bay in the 1960s with the vessel Vermont, he and his wife Marge were the prior owner of our house.

Wilfred A “Bill” Young. owned the troller Lollypop in the 60s and early 70s. He and his wife Wanda lived next door to our house, and my Dad originally came to Funter to help work on Bill’s house.

Harold Hargrave owned the vessels Janet, Merry Fortune, and Selig No. 1 in 1955. He later had the Mattie W. He was also the postmaster at Funter for some time, and lived near the cannery with his wife Mary. I will probably detail them more later.

James Hay had the vessel Janet and lived at Funter in 1945. From 1948 to 1951 the boat was listed as belonging to Anna Hargrave, then Harold Hargrave in 1952.

Gunner Ohman and wife Lazzette lived on the East shore of Funter in a log cabin that Gunner had built. He worked various jobs around the bay, including hand trolling (more on them later).

“Screaming Jack Lee” was a Funter Bay fisherman (probably a hand troller) who lived in a tent or vacant buildings in various places around Funter Bay. Harvey Smith’s description of him (via my Dad) was that he talked to himself a lot and you could hear him yelling all over the bay, screaming at his tools or his firewood for “fighting” him. A 1945 National Geographic article mentions some nicknames of Alaskan fishermen, and describes a “Screaming Jack” who got the nickname because he was always mad.

A fellow nicknamed “Shorty” had a log cabin and was supposedly building a fishing boat at Funter Bay, but forgot to leave room for the propeller shaft and left when someone pointed this out (photos of his cabin are in this post).

The Keelers (Floyd and George?), possibly an uncle and nephew, had a cabin near Clear Point. There were apparently several cabins here which were used by hand trollers. The Keelers might also have had a cabin near Hawk Inlet, and were also involved with logging. Part of one cabin by Clear Point was still standing in the late 90s and still showed some of the red paint.

Excerpt from a 1947 National Geographic article mentioning Funter Bay:

I may come across more information in the future and make an additional post or update this one. As always, if I have omitted or mistaken anything, please feel free to email me and let me know!

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts