While Northern Admiralty Island was never clearcut on an industrial scale the way the central section was, there have been occasional timber harvests in the Funter Bay area. Industrial logging was both helped and hindered by regulatory issues; creation of the Tongass National Forest in 1907 added some forest protections, but the Forest Service also earmarked large parts of National Forest to become foreign pulp exports. Private landowners had a few more options for local-use and some export harvests. General information and statistics on Alaskan logging is available here and here. A basic timeline of logging and timber regulation in Southeast Alaska in the 20th century is available here.

Handlogging tools at Funter Bay:

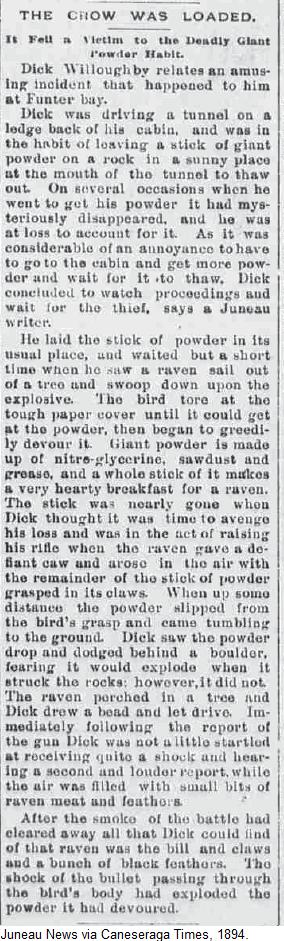

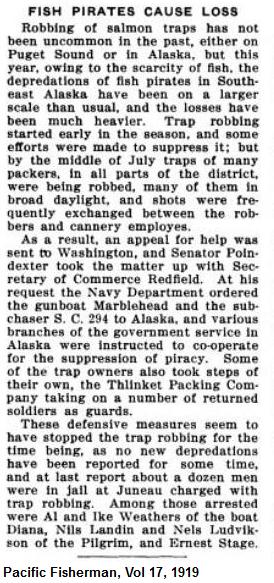

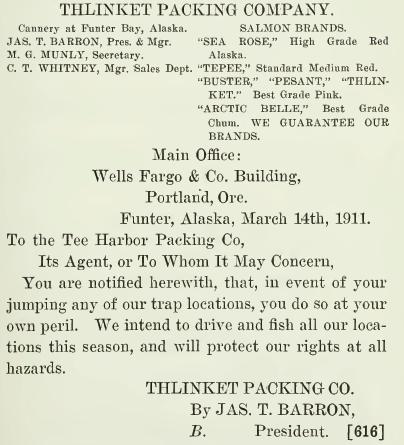

Early hand-logging operations in the 19th and early 20th century supplied logs for fish traps and pilings, shipping crates for canned salmon, wood for cannery and mine construction, and possibly fuel (although coal was more common as a fuel for steam boilers, possibly due to the high sap content of local spruce adversely affecting machinery). Most hand-logging operations were based from boats, the loggers would cut trees very close to the shoreline where they would fall into the water, then they would be tied into rafts and towed to lumber mills at Juneau and Douglas. Today there would not be much evidence of this forest-edge harvesting, but the practice probably explains why photos from the early 20th century show very few trees on the small islands in Funter Bay. These islands are heavily re-forested today, they would have been convenient places to cut old-growth spruce and float it away.

Despite the abundance of timber, some businesses imported lumber for construction, including the Funter Bay cannery (which brought in California Redwood beams), and other local buildings which were pre-fabricated and shipped up as packages. Certain woods like pine, and especially redwood, are more rot-resistant than the local spruce, and buildings made out of such woods have lasted longer in the damp environment. Spruce pilings driven near the shore or used as building footings were often soaked in tar to make them last longer.

Part of a shipping address stamped on lumber brought in from down south in the early 20th century:

Barry Roderick’s “Preliminary History of Admiralty Island” mentions a single cable-logging operation on the island in 1905 (where logs would be hooked to a cable and pulled or zip-lined to the beach). Later operations would have been more mechanized, with tractors and engines used to haul logs from stands of timber deeper in the woods. Of special interest were the old-growth cedar trees, prized for their rot resistance.

In 1911, the US Forest Service decided that clearcutting (AKA “Clean Cutting”) was the best method, supposedly it would allow sunlight to reach the forest floor and make new trees grow faster (in reality, clearcutting just creates big jungles of berry bushes, destroys wildlife habitat, and leaves the soil unprotected to wash away into salmon streams).

Sawmill equipment was delivered to Funter Bay in 1918 by the steamer Admiral Goodrich, probably for one of the mines. A 40hp steam-powered sawmill was reported in 1920.

In 1922 the Alaska Gastineau mine in Juneau purchased timber rights on Admiralty Island, but the sale was cancelled due to financing issues.

After WWII, the Forest Service attempted to entice pulp mill operations to Southeast Alaska. There were also some attempts to cut spruce for plywood and export full logs overseas, but most development seems to be devoted to grinding up the trees for pulp. These operations were heavily subsidized by the government, and still claimed to be operating at a loss. Local rumor has it that Japanese investors are stockpiling logs to sell back to the US once we’ve clearcut everything.

The Keelers who had a cabin near Clear Point (and possibly one at Hawk Inlet?) did some logging. The uncle-nephew team purchased a large two-man chainsaw. Unfortunately, the younger man was killed when one of the first trees they cut tree fell on him.

In the 1960s, local resident Ray Martin had a plan to log old-growth cedar from between the creeks at Crab Cove. His idea involved building a railroad from a dock at “The Point” up to the old-growth cedar stands between the creeks. The cedars would have been used for telephone poles. Ray apparently had many “get rich” schemes that never took off, and the logging operation was no different. He eventually landed in some legal trouble due to a shady stock deal with a company in Juneau.

The biggest logging project at Funter Bay was run by the Alaska Dano Mining Co in conjunction with Gary Lumber Co of Juneau. Spruce (and some Hemlock) was harvested from approximately 30-35 acres on and near Dano’s mining claims around 1969. Sources indicate that it was around 1.8 million board feet, mainly for export. In 1971, the US BLM transferred 33 acres to the state in the section which was logged, this could have been related to Dano’s operation, but I am not sure. The clearing resulting from Dano’s logging is still visible in satellite imagery, although its a much smaller scar than those left by the bigger industrial logging operations elsewhere on Admiralty Island.

Dano clearcut and logging road, 10 years after the timber harvest (color infrared image showing different vegetation types):

A Forest Service memo notes a timber sale of 222mbf (million board feet) in the Funter Bay area in 1969. That volume of timber would indicate an area of roughly 500 acres, much larger than the Dano clearcut. The appraisal price was 3 times higher than the average for Southeast Alaska, which could mean that cedar was the target rather than spruce. This could be related to Ray Martin’s plan, or to a late-60s plan to bring a large pulp mill to Juneau and clearcut the surrounding forests.

Today there are the remains of a piledriver at The Point, but I am not sure if this is specifically related to Ray Martin’s logging scheme, or simply left over from something else.

The other remains of Ray’s logging scheme include a mobile logging arch left on his property (which became our home). When my parents expanded our house, the arch was too heavy to move, so Dad incorporated it into the foundation of the deck!

A logging arch would be used in conjunction with a tractor, to raise one end of a log and then drag it somewhere for loading. Here’s a model of one. Here is a page showing logging arches in use. Here is a photo of a logging arch being used to assemble a log raft on an Alaskan beach.

Dad believes this was Ray’s tractor, a Fordson made by the Ford Motor Company in Detroit:

Fordson tractors were quite popular in Alaska. It also seems to have been somewhat common to turn them into small railway locomotives, everywhere from Nome to New Zealand.

Here’s a Fordson-based locomotive in Nome, AK:

Here’s the low-budget model, with the rail made of logs (a “pole road”) and the wheels apparently just big flanged rims. And here’s a whole bunch more. A salt mining company once built a monorail using Fordson tractor motors!

Here is a mention of another small railroad in Southeast Alaska, with a Fordson locomotive. That site also had a Fordson-powered sawmill:

Ray Martin had a marine railway at the property, which included some tracks leading from the beach up to the house, and some wheels and axles. This would have been used to haul his boat out for storage and repairs, but maybe he planned to build his own logging railroad using some of this equipment as a starting point? By the 1950s, mines in Southeast Alaska were switching from railways and tramways to gravel roads, and surplus rail equipment would probably have been available cheaply.

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts