Alaska’s history is filled with shady characters, dastardly deeds, and unsolved mysteries. Almost every town, mining camp, or cannery has its tales of murder, larceny, or swindles of one sort or another. In past installments of Funter Bay History, I’ve mentioned some of the criminal activities which went on in the area, including bootlegging, fish piracy, and other shenanigans. This post covers some more serious crimes, as well as various lesser incidents and shady dealings. Some of these are snippets from newspaper articles which are long on sensationalism and short on fact, multiple sources have been consulted when possible. Unfortunately there is not always follow-up information or detail readily available, so the outcome of some of these cases is not clear.

——————————————————

A murder on August 18th of 1894 reportedly involved two local prospectors. Archie Shelp and George Cleveland were accused of illegally selling whiskey to Natives, resulting in a drunken killing (or perhaps two killings, sources differ). The defendants claimed they were in or near Funter Bay during the supposed events, not at Chilkoot (Haines) where the murder took place. An 1895 article described how “two Indians bit the dust” during a drinking bout with two Swedes, which may or may not refer to the same case. Gus Lundgren, who had been camping at Funter, testified that the two had been there on August 16th-17th of 1894. The defense claimed that they could not have sailed to Chilkoot in less than three days (from my own sailing experience, I would say it could be done in one long day with favorable winds). The prosecutor pointed out that there was no evidence Shelp and Cleveland were prospecting “with pan and shovel” as they claimed, and instead were “prospecting for the aboriginal native” with keg and tin cup. The two were convicted of illicit alcohol sales, and appealed.

——————————————————

An underground fight between miners at Funter Bay was reported in the Alaska Mining Record on June 10, 1896. William Williamson (Brother of Sandy Williamson) was supposedly attacked by Billy George, aka “Indian Charley”, and had a piece bitten out of his lip. The young Williamson had no experience in drilling and refused to strike double-handed. George, who had a “record as a biter” was upset with this and attacked him. After a 20-minute fight which left hair plastered on the walls of the shaft, the attacker fled. Billy George then gathered up his family and possessions and left in a canoe. (Excerpt in Barry Roderick’s A Preliminary History of Admiralty Island).

——————————————————

A “bloody battle”, and the first killing of an on-duty law enforcement officer in Alaska occurred near Funter Bay in 1897. That January, a “notorious young desperado” named William Thomas “Slim” Birch had been locked in the city jail, convicted of “mayhem”. The charge stemmed from a bar brawl in which Birch had bitten off part of Henry Osborne’s nose and ear. Birch was said to possess a “temper that runs wild” when under the influence of alcohol, frequently landing him in trouble. Despite his temper, “Slim” was a popular fellow in Juneau. He and his brothers had made some money early in the gold rush, partly through mining and perhaps partly through smuggling. They owned the Douglas City Hotel and Cafe, which featured a lively saloon, and had the support of many local miners. The night before Slim was to be shipped South to prison, a group of masked men staged a jailbreak, locking the jailer in his own cell. The group then fled in a sloop to Admiralty Island.

Within weeks an informant reported Birch and co hiding out in a cabin on Bear Creek, 3 miles from the Juneau side of Admiralty Island (About 1-1.5 miles from Funter Bay). A posse consisting of two deputy US Marshals, the jailer, a jail guard, and an “Indian Policeman” set out in pursuit. After a tugboat trip from Juneau, followed by a long and grueling hike through snow and ice, the party reached the cabin. Accounts vary as to what happened next. One story was that Slim snuck out of the cabin and ambushed the deputies from high ground. Others say the fugitives fired through the door as the lawmen knocked on it. Other accounts say the officers found Birch and his accomplices sleeping and fired first.

“He is a desperate man and the deputies knew it, so they began shooting into the cabin, taking great chances on getting their man alive. Birch opened his cabin door and began to shoot with two revolvers” (from San Francisco Call)

While the truth of who fired first was not clear, all accounts show that the posse had the worst of the ensuing shootout. Jail Guard Bayes was hit and ran back towards the beach despite bleeding profusely from both legs. Deputy Marshal William C. Watts attempted to take cover behind a fallen tree but found the rotten wood a poor shield. Deputy Hale exchanged shots with Slim Birch, then came under fire from the cabin. Struck in the chest as he tried to reach Watts, Hale staggered and fell into a small stream. He managed to pull himself out and make it out of range. Jailer Lindquist hid behind a tree as it was riddled with bullets, and was hit in the eye by flying bark. The Native policeman, Sam Johnson, was the only one of the posse to remain uninjured. Johnson reportedly saw Birch and three or four other men inside the cabin, firing from “loopholes” between the logs. Watts was reportedly hit several more times during the gunfight. The other lawmen retreated, leaving the injured Watts behind. Hale’s wounds were said to be serious, but he eventually recovered.

After fleeing back to Juneau, the officers gathered a new posse of 20 men, along with a detachment of US Marines. A search party from “the neighboring cannery settlement” also hiked in to the cabin (The Funter cannery did not yet exist, but several others were in the area). Watt’s body was found “frozen stiff in the snow, where his cowardly companions had left him”. Several days searching resulted in nothing but frostbite for the posse members, and additional men came in from Sitka to join the manhunt. An investigation of the cabin found the floor “liberally scattered” with 38-90 and 45-70 rifle shells, and several firing loopholes cut into the logs to fortify the position. Also revealed were 50lbs of hidden gunpowder, thought to be part of a bank robbery scheme. Hiram Schell, one of Birch’s accomplices, had previously been in jail for gold robbery, the tale of which is a ridiculous adventure of its own and also involves a stop at Funter Bay.

The search ended when two cannery employees named Cheney and Olson discovered the heavily-armed Birch and Schell sleeping in dense underbrush. They reportedly had pistols in hand, requiring a stealthy approach to avoid waking them. The two cannery men crept up to a ledge above the fugitives, then leapt down and were able to manacle them after a brief struggle. The captors received a $500 reward for their efforts. The slain Deputy Watts had been a popular and well-known officer in Alaska, and tempers were high on all sides. The prisoners were taken to the Sitka jail for their own safety, as there was fear of encountering a lynch mob in Juneau.

At their trial for murder, Birch and Schell claimed self defense, and the contradictory statements from the lawmen confused jurors. Birch’s brothers and local miners raised enough money to bring in “prominent” defense attorneys from Seattle. The defendants claimed that the deputies had not announced themselves before shooting, and they were thus responding to an unprovoked attack from unknown assailants. There was debate over the cause of Watt’s death, be it from his wounds, freezing, or both. Birch even claimed that he had been kidnapped from the jail and had not meant to escape in the first place! Eventually the pair were found not guilty of murdering Deputy Marshal Watts, an “outrageous” verdict which horrified the governor of Alaska. None of the other offenders were ever found, although a belt marked “W.H. Phillips” was recovered from the cabin.

Slim did end up serving 3 years at San Quentin for the original mayhem charge. He moved to Prescott, Arizona in 1902 and opened a saloon with his brothers Sidney “Kid” and Robert “Bob” Birch. Slim continued to get into bar brawls, including a 1908 affair in which all three brothers broke up a card shark scheme with flying fists. They also ran afoul of the law with gambling fines and prohibition violations. “Slim” died in 1952.

-“Bloody Battle in Alaska; Between Desperadoes and a Marshal’s Posse” The Record-Union (Sacramento), 4 Feb 1897.

-“Capture of Slim Birch” San Francisco Call, 4 February 1897

-Fletcher, Amy. “Whitman shines light on a dark chapter of Alaska history”. Juneau Empire, 27 Oct 2013. (link)

-Hunt, William. “Distant Justice: Policing the Alaskan Frontier”. OK: U of OK Press, 1987.

-Roderick, Barry. “A Preliminary History of Admiralty Island” Douglas, AK, 1982.

-“To Plead for an Alaska Outlaw” San Francisco Call, 28 Feb 1897

-Wilbanks, William. “Forgotten Heroes: Police Officers Killed in Alaska, 1850-1997”. Turner Publishing Co, 1999. (link)

——————————————————

An article in the Juneau Record-Miner from July 11, 1907 had the headline “LOOKS LIKE MURDER”. A man named Herman Smith had disappeared under suspicious circumstances, with “strong indications that foul murder has been done somewhere between Douglas and Funter Bay”. Smith’s boat the “O.K.” ran out of gas at Cordwood Creek on the way to pick up fish, so he borrowed a small boat from Harry Scott at a Funter Bay fishing station. After getting fuel he left Douglas to return to the O.K., but then vanished. The article stated that “An Indian woman claims to have seen him murdered in the vicinity of Cordwood creek”. Reportedly missing were $130 cash and a month’s worth of provisions.

——————————————————

A fugitive from Sitka by the name of Ah-kee was pursued and overtaken at Funter Bay in July of 1909, and brought to court by Deputy Marshal Shoup (Shoup is also mentioned in a previous post).

——————————————————

In November of 1912, a miner named Martin Damourette was arrested and charged with larceny, accused by his mining partner L.C. Wilson. The two had stored equipment at their Funter Bay claim, and Damourette supposedly stole it while Wilson was absent. The court dismissed the criminal case almost immediately. Wilson filed a civil suit, but Damourette “ducked out of town” for Seattle the same night.

——————————————————

Another disappearance occurred at or near Funter Bay in 1915. Robert McGregor was reported missing by crew of the Santa Rita the morning after arriving at Funter Bay. He was a carpenter from Gypsum who had worked at various mines and camps around Alaska. Cannery officials supposed that he wandered off in the dark and became lost, but a search of the area found nothing.

——————————————————

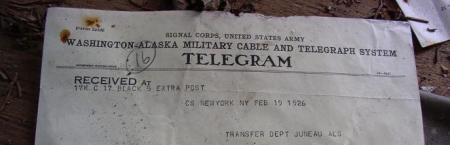

Illicit booze continued to be an issue in the area, especially since it could sometimes be mail-ordered!

——————————————————

In October of 1917, two men named Thorensen and Okerberg were indited for furnishing liquor to Natives at Funter Bay.

——————————————————

In 1922 the body of Oscar “Terrible Swede” Lindberg was found burned to death on the beach at Bear Creek, across the island from Funter Bay. The case is filed under “Murders” in the Bayers notes.

——————————————————

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts