In this edition of Funter Bay History, I’ve compiled some statistics and information regarding the population and economy of the area. Funter Bay has variously been described as a town, a village, a ghost town, or simply a location with a cannery and mines. Knowing some numbers and comparative sizes might help place things in context.

__________________________________

Firstly, some background information. Alaska’s modern community designations differ from many other states. There are several types of municipalities defined for legal and tax purposes, including “Home Rule Cities” and “General Law Cities”, of which there are either first or second class cities. There are also Home Rule and General Law Boroughs (a borough is equivalent to a lower-48 county). Alaska is also unique in having an “Unorganized Borough“, more than half of the state is simply not part of any municipal entity, and thus has no property tax, sales tax, or any services below the state level. Funter Bay has long been a part of the Unorganized Borough. Juneau occasionally attempts to annex Funter Bay, annexation has been fought off by local residents on the grounds that they would pay property tax but would not receive any city services.

Another tricky detail is that some households in Alaska are migratory or seasonal (both in and outside the state). Residency reporting is sometimes based on economic reasons (such as inclusion in a school district or eligibility for Permanent Fund Dividends), and not on a person or family’s most common physical location. A seasonal fishing community may wish to count summer fishermen as part of their population, while those fishermen may report a different place of residence on their taxes. Funter Bay has always had a larger population in the summer, be it Tlingit fish camp residents, cannery workers, seasonal fishermen, or vacationing cabin owners.

Keeping in mind that these numbers may be “fuzzy”, here is some comparison data from the 2010 census. Partly from this document.

Bettles, the smallest “Second Class City”, has a reported population of 12.

Pelican, the smallest “First Class City” has a reported population of 88.

Nenana, the smallest “Home Rule City” has a reported population of 378.

The total population of Alaska in 2010 was 710,231. The three largest cities are Anchorage (291,826), Fairbanks (31,535), and Juneau (31,275). They quickly get a lot smaller.

There are also “Census-Designated Places”, along the lines of an unincorporated town in the Lower 48. These communities may have some public facilities, and communities with more than 25 residents receive some state money for utilities and infrastructure. The population may live in a discrete area or be spread out around some center such as a post office or store. Some examples close to Funter Bay are:

Elfin Cove – reported population of 20 in 2010. (This is generally considered a “town” by most locals and population swells to 100+ in the summer). In 1939 Elfin Cove had about 65 residents and was referred to as a “village”.

Excursion Inlet – reported population of 12 in 2010.

Whitestone Logging Camp – reported population of 17 in 2010

__________________________________

Now, on to the numbers for Funter Bay:

The 1890 census listed 25 residents at Funter:

A 1903 congressional convention in Juneau solicited delegates from around the state based on population. Funter Bay sent one delegate, the same number as Hoonah, Angoon, and Petersburg. Sitka sent 3, Fairbanks had 4, Juneau itself had 10.

Summer population varied based on the number of workers brought in by the cannery. A 1904 article mentions “30 odd” Chinese employees traveling to Funter Bay to work at the cannery that season (“Chinese for Funter Bay”, Daily Alaska Dispatch (Juneau) 2 May 1904) A 1906 brief in the Dispatch mentions a can-making crew of 73 Chinese workers enroute to Funter Bay. In 1910 the Dispatch reported 84 Chinese workers.

A 1905 article reported an “Indian Village of 400” at Funter Bay, with around 60 native employees working at the cannery. This “village” (also described here) was likely a summer fish camp for Tlingit natives. Some documents refer to it as housing for cannery employees. Various histories report that Funter was used for seasonal subsistence, but was not a permanent village site. Other reports indicate that the “village” or camp site moved around the bay as various white settlers or industries interacted or interfered with it. An interview with Elder Dave Wallace stated that there was no village at Funter Bay, but it was a good place for king salmon and berries. It was claimed by the Wooshkeetaan clan, part of the Auk Kwáan, and was called Shakananaxwk’.

Some Tlingit employees at the cannery in 1908 (more here):

The 1910 US Census shows 70 people at Funter Bay. It was conducted in May when the cannery’s seasonal labor force was on hand. A few people are listed as independent fishermen. The microfilm quality is unfortunately quite poor, so not much else can be determined from it.

In 1912, merchandise valued at $78,933 was shipped to Funter Bay. (Per Alaska 1912 Commerce report, Daily Alaska Dispatch, 1 Feb 1913)

In 1916, the value of merchandise shipped to Funter Bay was $128,471 (Per “Report of Collector of Customs” Daily Alaska Dispatch (Juneau) 18 Feb 1917).

In 1918, the merchandise shipped to Funter totaled $267,697 (DA Dispatch 4 Feb 1919)

The Census of Oct 11, 1929 found 50 people at Funter Bay. The handwritten notes are somewhat hard to read, but show that approximately 12 residents were fishermen, 11 were miners, one was a logger, one was a mining engineer, and one was a bookkeeper at a mine. The cannery’s seasonal workforce had left for the winter, leaving a cashier at the store, as well as the cook and his family. About 9 women are listed with the occupation “Housewife”, and about 7 children are listed.

1929 Census records for Funter Bay ( 2 pages):

By 1939, Funter Bay was not being counted as a separate location, but was lumped into the Juneau census area (and later, the rather oddly-drawn Skagway-Angoon-Tenakee census area). The 1940 census reported 98 residents on “Admiralty Islands”, excluding Angoon and Killisnoo, but possibly including Tyee, Gambier Bay, Hawk Inlet, and other canneries.

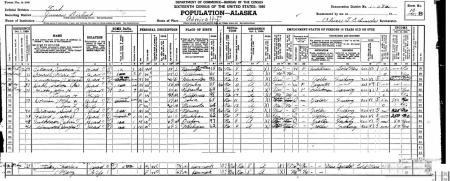

The following 1939 Census records seem to be noted “Funter Bay” on the extreme left, and includes 14 people:

In 1979, Funter Bay reportedly had a year-round population of 14, and a seasonal population of 25.

By the late 1990s the population hovered around 10 year-round residents. (I recall a census taker in 1990 being dropped off by plane and planning to walk around the entire bay, unaware that 90% of the visible cabins were vacant and that the trails shown on maps were no longer passable).

So, depending on the accuracy and reliability of the reporting agencies, Funter Bay has historically had a summer high of between 100-500 residents, and a high winter population of around 50. It has never been a bustling metropolis, but was certainly on a par and occasionally rivaled other established Alaskan communities.

Posted by saveitforparts

Posted by saveitforparts